This week involved a disconcerting amount of physical reality.

People materialised in actual rooms. Ideas escaped their Google Docs and did things to other humans in real time. Work happened in ways that required shoes—sometimes even presentable ones. Collaboration, usually a distributed affair mediated by timestamps and emoji reactions, briefly acquired mass and occupied three-dimensional space. It was all very analogue, in that faintly unnerving way analogue things are when you’ve forgotten they exist.

I hadn’t quite realised how thoroughly my working life now exists as a theoretical proposition rather than a physical practice until this week gently but firmly dragged me back into corporeal form.

This week at work

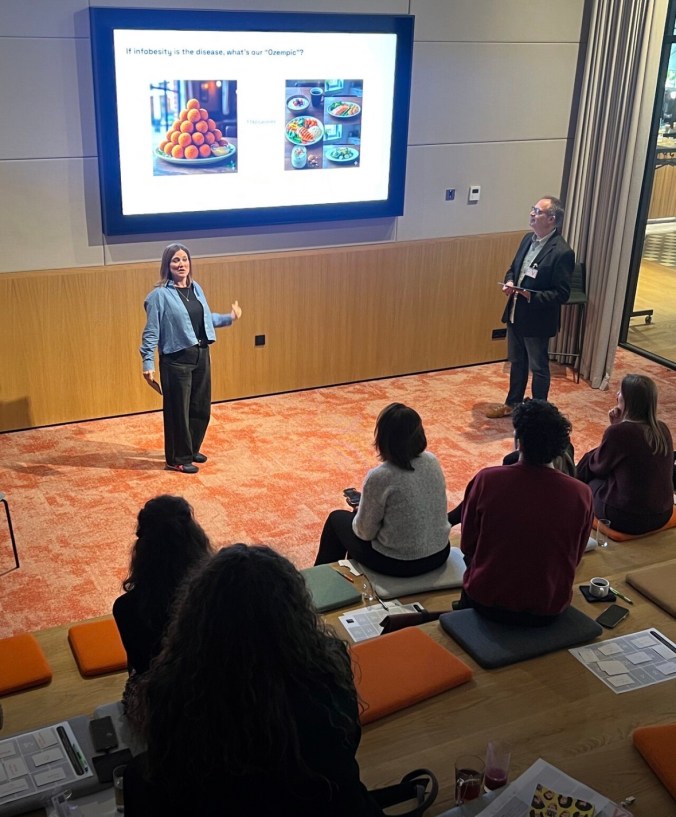

We delivered an ‘infobesity’ workshop with Swoop at ING—their term for information overload, and a very good one, which resonated immediately with me, a middle aged woman who has tried and failed at every diet known to (wo) man.

The morning brought together a collection of comms people from pleasingly complex organisations. And I’ll admit it: I love running workshops. The architecture of ideas, the careful choreography, that electric moment when something actually lands in a room full of people who’ve heard everything before. It went well. People were open, honest, collaborative, generous with their ideas and tolerant of our extended metaphors. And that’s the best I can hope for.

It was also my first public outing of the “Infozempic” concept, which I’d been nursing like a potentially embarrassing joke at a wedding. The collective intake of breath when I said it—that visceral ohhh—was gratifying in a way that probably says something unflattering about me. The metaphor hit a nerve. Possibly because everyone’s drowning and I just named the water.

The feedback was effusive enough that I immediately carved out time to write an extensive blog post on the same theme. Yes, responding to a workshop about information restraint by producing more information is ironic in a way that would make Alanis Morissette weep. But when an idea has heat, you chase it. Better a considered piece written in the moment than another half-arsed thread abandoned at 11pm.

With Jon in town for the workshop, we seized the opportunity to tick off two remarkably adult tasks. First: professional photographs. Despite speaking daily across international borders, we’ve somehow amassed approximately zero visual evidence of existing in the same postcode. Given the book’s imminent arrival, it seemed prudent to acquire proof that we’re not an elaborate catfishing scheme before journalists start asking reasonable questions about whether we’ve ever actually met.

Second: actual strategic planning for book promotion. We discussed what we want to say, who might conceivably care, and how to avoid becoming just another desperate voice howling into the digital void come launch day. The bar is low, but we’re hoping to clear it.

Mid-week brought a pitch to a potential new client. Early omens were promising, which means we’re now in that delightful purgatory between “I think that went well?” and “now we wait while they ghost us or don’t.”

Simultaneously, we’re spinning up two new projects, doing the unglamorous but essential work of actually understanding the organisations before swanning in with hot takes. It’s the bit that doesn’t make for good anecdotes, but it’s where most projects are quietly sentenced to success or failure.

And the book continues its stately procession through the publisher’s approval machinery, advancing without us like a child you’ve sent off to university. It’s oddly pleasant and faintly unsettling to watch something you’ve made take on independent life, trundling along tracks you’re no longer steering.

Also this week

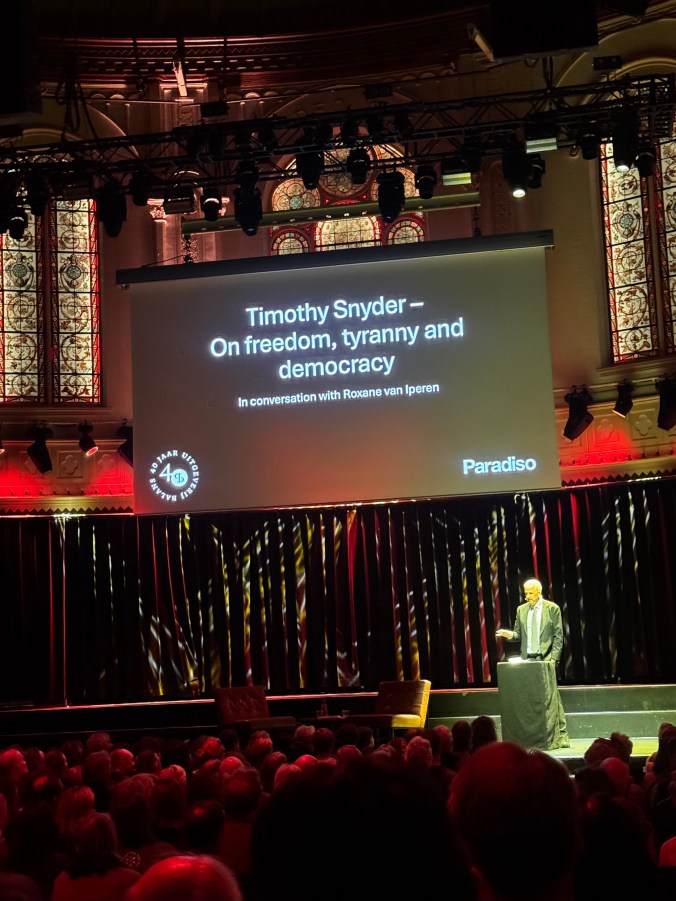

I also went to hear Timothy Snyder talk about tyranny and freedom, which is exactly the sort of thing a normal person voluntarily does on a weeknight. I left genuinely uncertain whether I felt enlightened or simply more anxious about everything—probably both, which I suspect was rather the point. He positioned Ukraine not as just another crisis to scroll past between doom updates, but as the philosophical hinge point for Europe. No pressure.

What lingered was his insistence that resistance requires an actual vision of what you’re for, not just what you’re against. Freedom, properly understood, isn’t just the absence of interference—that thin, negative American definition—but the conditions that let people become what they want to be. Europe, he noted, practices this reasonably well while barely mentioning it, which leaves us ideologically underprepared when someone shows up to actively dismantle it.

The framing stuff was grimly compelling: Trump understanding sovereignty purely as property rights, immigration as pretext for building an unaccountable federal force, oligarchy and surveillance capitalism aligning beautifully with authoritarianism. None of it felt theoretical. All of it had the unfortunate coherence of something that’s already happening, which—Snyder argued—is exactly what makes it resistable if you can see the pattern.

He was bracingly blunt about media deference letting US presidents set Europe’s agenda days in advance. And he positioned history not as a warning label we slap on things, but as a reservoir of actual meaning alongside art and culture. Protest needs art, he said, especially now that AI can churn out infinite aesthetic slop. Human unpredictability still counts for something.

Oddly, the hopeful bit came last: talk to people in real life, including the racist uncle. Don’t try to win—plant seeds. Build coalitions with people you agree with 85% of the time, not 100%. Fascism is never defeated intellectually; you have to actually win things. Elections, institutions, minds, power.

I didn’t leave reassured. But I did leave thinking the catastrophe is at least comprehensible, which means it’s not inevitable. Small mercies.

Connections

Ahead of the workshop, with Jon and the Swoop team already in Amsterdam, I did something dangerously close to networking: I organised drinks for comms and digital workplace people. Actual, three-dimensional humans gathered in a bar—a concept that still feels faintly experimental post-pandemic.

It was genuinely lovely meeting people I’ve known online for years but never actually stood near, plus a few I’d met once years ago, and had since reverted to being profile pictures who occasionally like my posts. Always a relief when your LinkedIn feed materialises as actual thoughtful, funny folks rather than the corporate avatars you’d half-convinced yourself they were. We complained about vendors, and I demonstrated the ancient Dutch art of eating bitterballen without incinerating your entire mouth (secret: patience bordering on the superhuman, waiting until the molten core drops below lava temperature).

Coverage

I appeared on the WB-40 Podcast this week, talking nomad working with Lisa Riemers—podcast host and regular Lithos co-conspirator. The conversation emerged after she’d read my Yearnote, specifically the bit cataloguing the increasingly ridiculous places I’d worked from last year, and decided this warranted interrogation.

Her challenge was entirely fair: just because you can work from a capsule hotel in Fukuoka doesn’t mean you should, or that anyone else wants to. What about people who need routine, a proper desk, the psychological comfort of consistency? I didn’t argue. In fact, I have a half-finished blog post festering in my drafts that’s essentially a litany of everything that doesn’t work about nomad working—the friction, the exhaustion, the endless low-level admin of simply existing somewhere new.

But that doesn’t make it pointless. Working from Japan isn’t viable for most people—it’s barely viable for me much of the time. People like me are early adopters operating at the extreme edges of what current work systems can tolerate. And that’s precisely the point. If you can make work function for nomads, you make it work better for a vastly larger group: parents, carers, people nowhere near major cities, people whose lives categorically refuse to conform to a 9-to-5 tethered to a single postcode.

We already have most of the tools. What we haven’t managed is loosening our death grip on time the way we’ve started—barely—to loosen it on place. Until we do, we’ll keep extracting a fraction of the potential value while excluding far more people than necessary. But at least we’ll all be in the office on Tuesdays.

This week in photos