Mondo are one of the most talked-about new players on the consumer/retail banking block (just this month they reached a $1m crowdfunding target in 96 seconds), so I was delighted to get a place on their Alpha. Here’s a few early thoughts and observations on my experience and what it might signal for the future of FinTech.

It didn’t start well, for me. Specifically, I managed to destroy a coat rack within moments of arriving in their offices, sending a pile of jackets and scarves to the floor. But within half an hour I was up and running with an app and a fluorescent pre-paid Mastercard, ready to take a look at the future of banking.

As a nerdy consumer I’ve been looking at the future of banking for a long time now — I think I got my first online bank account around the turn of the century, which was roughly the time I started earning money. For most part from an experience point of view the future of banking tends to look a lot like other online user experiences did five years previously*.

* Except my bank account in Asia. That’s more like every other user experience in 2001.

So I’d agree this is a market ripe for disruption, and that customer needs are probably better served by attempting to build a new bank from the bottom-up, based around user need, than building marginally nicer front ends for terrible legacy infrastructure.

Mondo is one of a number of UK startups attempting to do that. Fellow challenger Atom has a banking licence, unlike Mondo, but is yet to have a releasable product. Mondo is taking the reverse tack, developing its app-based bank in public, offering a pre-paid card to several thousand Alpha users and asking for feedback, while working with regulators behind the scenes on getting their banking licence.

I’ve seen the future. It’s pink with a liberal sprinkling of emoji.

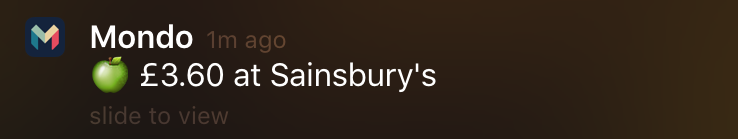

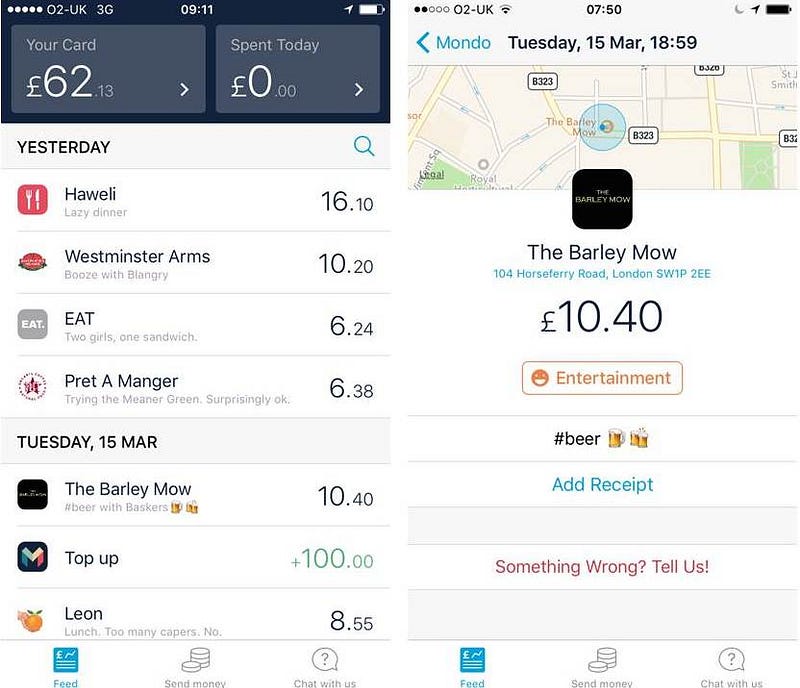

Mondo is, in short, a card and an app, with ambitions to turn this into a full service retail bank in time. The app itself is neat; every time I use the card, I get an alert on Mondo, replete with carefully-chosen emoji, before the sales assistant has printed the receipt. These guys must spend a scary amount of time choosing emoji.

It’s a pre-paid, luminous pink Mastercard, and while topping up is simple this does limit its usefulness as there’s no auto top-up option. I was about to pay for a few things at the weekend but only had £20 left on the card; as Hammersmith is a weird mobile phone coverage blackspot I couldn’t add money to it, and had to fall back on my regular debit card. It doesn’t yet work with ApplePay, but the team have said this is on its way.

As it’s linked to your phone, it’s smart enough to work out where you are and how this might impact your spending. If you’re in Singapore and but your card’s being used in Swansea, it can let you know immediately. Which is refreshing change from ham-fistededly blocking your card every time you travel.

The app makes it easy to see what I’ve spent by vendor and category, and gives me the option of adding tags, notes, receipt images and so on to each transaction. It’s easy to see my balance and spending at a glance. A particularly nice feature is the ability to freeze the card when you can’t find it, and unfreeze again when found — rather than the big banks’ standard option of cancelling the card and waiting a long, cashless, cardless week to have a new one sent through the post.

And these are all great features. In fact, if I were my flaky 21-year-old self — on a tight budget and prone to losing my cards — the features offered by Mondo would easily tempt me to switch to it as my main vehicle for day-to-day spending.

But I am not 21. While Mondo does give me a vague sense of guilt over my cumulative spend in sandwich chains, I’m at a point in my life where I’m lucky enough not to be too concerned about £10 spent on wine or nail polish. My digital banking needs are different now I’m a proper grown-up.

I have savings. I’d like to have more savings, and I’d like my bank to help me to make saving a habit rather than an afterthought. Knowing I spent £6.38 on juice and yoghurt is all well and good, but if my bank could tell me, at the right time, that if I bought fewer cakes I could pay my mortgage off two months earlier, that’s useful to me.

I like data, but for my accounts data to work for me I need to be able to see it in one place, and I need it to be interoperable. Spend-specific emojis make me smile, but I can’t use them to reconcile transactions in my freelancer accounting software. My regular bank account has an API and allows me to download transaction data so I can interrogate it.

I also like free stuff. I chose my bank account when I began university, because they gave me a hefty fee-free overdraft and a student railcard. Like most people I have never bothered to change my bank account since. These days I have a reasonable credit rating and a taste for far-flung destinations, so I do all my spending via my credit card in order to build up airline points. A year’s worth of hotel bills, work expenses and pub visits were enough to get me two free flights via my credit card’s reward scheme. I’m willing to put up with some seriously bad UX in return for a free holiday.

Banks for brogrammers, by brogrammers

I like Mondo, and I like what they’re trying to do. What they do, they doreally well. For payments and day-to-day usage, its UI, UX and FX is streets ahead of my high street bank.

But right now it isn’t enough to make it my everyday bank, because it doesn’t (yet) meet my needs as a solvent thirty-something woman.

In that respect, it’s not so different from other startups, very many of which have cropped up to solve the problems of the unrepresentative sample of people who build apps. From Uber to Airbnb to laundry pick-up and gas delivery services, Silicon Valley et al are focused on solving problems faced by people like themselves.

To be fair to Mondo, they have at least recognised this and sought to get more women on their Alpha in order to get a wider range of feedback. But if any company truly wants to transform its sector, it needs to solve the problems of a full cross-sector of consumers. Elderly ones with rubbish phones and failing eyesight. Poor, underbanked ones. Even boring ones like me with low-risk investment needs and unsexy pension arrangements.

As my 300 Seconds co-founder Hadley Beeman said at our opening event three years ago, if we want to change the world, we need a good cross-section of humanity to be involved at every stage — to articulate their user needs, and develop products to meet those needs.

If you want to change banking, you need to solve for more than coffee budgeting.

Banking is a fully digitisable business. In a business which doesn’t deal in tangible things trust is critical. This gives traditional banks a major advantage; most people prefer to entrust their money to an FSCS-backed institution than a startup.

My short experiment with Mondo has shown how quickly a challenger bank can win the user experience battle. While my high street bank has the edge in terms of both functionality and trust for now, challengers are engaging with regulators and fast catching up.

Where traditional banks can maintain an edge is their knowledge of and relationships with a much broader range of customers, recognising that customers don’t just need an app, but a range of products and services to meet their diverse needs at different life stages. Banks have access to a wealth of data on customer behaviour and needs that they could use to develop smarter, easier solutions for customers.

Yet right now neither side seems to be getting it quite right. Startups are focused on solving too narrow a set of user needs to serve the mass market, while traditional banks are attempting to make old systems and structures deliver better digital experiences and coming up short, and resting on their laurels in the hope customers are too lazy or untrusting to try the competition.

Trust in banking and finance continues to lag far behind that of technology firms. Startups are rapidly breaking down regulatory obstacles, gaining consumer trust and building brand recognition. While what Mondo et al haven’t yet got a strong enough product to make me ditch my bank, if they can beef up their offering and combine this with quality user experience, they’ll get my money soon.

So Ribot made human emotion central to the

So Ribot made human emotion central to the