Consulting is a game played over years, not weeks. Some engagements are about architecture and impact. Others are about helping procurement tick a box before buying what they were always going to buy.

The ratio varies depending on market conditions, how disciplined you are about qualifying leads, and whether you’re willing to walk away from bad-fit work when the pipeline looks thin. Most small consultancies say they’re selective. Most small consultancies also have mortgages.

The discipline is remembering that not every loss is a mistake — but some are instructive.

This week at work

We had the official kickoff with a new client this week, and it’s one of those projects that makes you feel the stretch in a good way. Ambitious scope. A platform that’s new not just to us, but to the industry. And a brief that isn’t “launch an intranet” but “design the foundations for an agentic-first communication architecture.”

Content structured for humans and AI agents. Governance designed with automation in mind, not bolted on afterwards. Distribution built around orchestration rather than broadcast.

It’s rare, in this field, to work on something that feels genuinely new. Most of what we do is evolutionary — cleaning up legacy, untangling compromises, retrofitting governance onto yesterday’s shortcuts. This feels different. I’m relishing it.

Less positively, we were also knocked back on a proposal this week. One we’d invested in properly.

We were recommended in by a former client. We had multiple constructive calls. We built demos. We did due diligence. We produced a draft project plan — explicitly positioned as a working document for discussion.

The moment that draft landed, the temperature changed. Silence.

Then, weeks later: “We’ve decided on a change of direction.”

Reader: there was no change of direction. There was a decision already made. Our work simply helped validate it — or more accurately, helped their procurement team tick the “we got an alternative proposal” box before buying what they’d already decided to buy.

This is a pattern small consultancies recognise instantly. You’re invited in to cost the hard bits — content, governance, migration, adoption — so a glossy platform decision can survive CFO scrutiny. You expose the complexity. You quantify the risk. You make the organisational reality visible.

And then that thinking becomes unpaid pre-sales support for someone else’s commission.

Let’s call it what it is: extracting expertise without paying for it.

It’s short-termism disguised as process. And it disproportionately hurts smaller firms, because speculative proposal work is not a rounding error for us. It’s days of senior time. It’s pulling in partners. It’s opportunity cost.

What makes it worse is the economics.

The organisation hasn’t “saved money.” They’ve simply shifted where it’s spent — typically towards a vendor backed by private equity, buoyed by marketing budgets, promising “turnkey” simplicity that rarely lives up to reality.

They will still need content. They will still need governance. They will still need adoption work. Software does not generate clear ownership, accurate information or disciplined lifecycle management by magic. It just generates invoices more efficiently.

You can underpay for advice or overpay for consequences. The invoice arrives either way.

The only guaranteed winner in this dynamic is the vendor.

And that’s the part that leaves a faint sadness beneath the anger. Because we actually want these programmes to succeed. We care about the long-term architecture, not the quarter’s sales target. Which is precisely why we’re less convenient to hire.

But then the very next day, we got the green light on a new project with a far more interesting client. One where the conversations are candid. Where the problem is complex in the right way. Where substance beats theatre. Where we’re building something durable, not decorative.

But that’s the gig. One minute you’re being picked clean like a buffet carcass by people who consider “market research” a legitimate use of your skull contents. The next, you’re signing something that actually matters. The whiplash is simply the cost of staying solvent.

Also this week

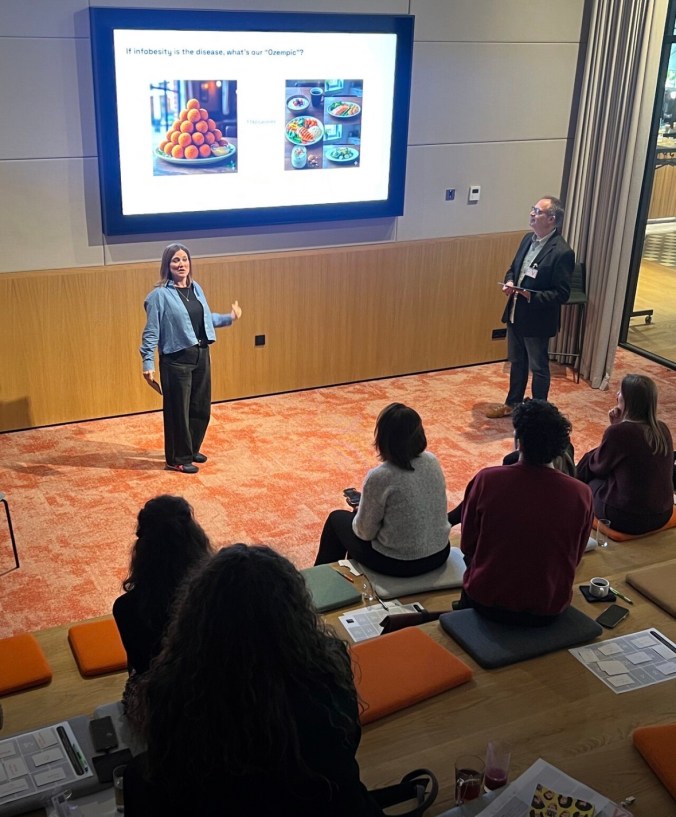

Accidentally had a week of AI immersion. Three sessions, three lenses — but a surprisingly consistent message.

The first focused on protecting our “human OS”: judgment, stance, taste, sense-making and responsibility. AI can inform and accelerate. It cannot own consequences. (Though it’s certainly convenient for those who’d prefer not to.)

The second, at Work/Shift, made the uncomfortable observation that individual productivity gains aren’t translating into organisational value. People are faster. Teams are not. AI is amplifying whatever system it enters — including half-finished transformations and fuzzy accountability. If your organisation isn’t legible to itself, it certainly won’t be legible to machines.

Kim England shared an instructive example from Pearson: a five-day reduction in customer response time only happened after fixing broken processes. AI layered on top of clarity works; AI layered on top of chaos simply scales it at premium margins.

The third was the launch of IABC’s AI Special Interest Group — communicators recognising that we’re now in the room for governance and ethics whether we like it or not. The tone was less “how do we deploy this?” and more “how do we remain human while we do?”

Across all three, the pattern was clear.

There’s a growing murmur that AI isn’t living up to enterprise hype. Gains are localised, uneven, individual. The transformation dividend hasn’t shown up in the quarterly numbers.

But that often precedes normalisation. The dip before the Plateau of Productivity. Or the bit where everyone stops mentioning the initiative while still paying the licence fees. Which makes this moment less about disappointment and more about architecture.

If AI is going to move beyond personal productivity hacks and into collective capability, the foundations matter. Governance. Context. Team coherence. Legible decision-making.

In other words: exactly the sort of agentic-first communication architecture we kicked off this week. Funny how these things converge.

Consuming

Work didn’t leave much time for TV or reading this week, but I did re-watch the original Star Wars in preparation for our forthcoming trip to actual Tatooine.

Not “inspired by.” Not “filmed near.” Actual Tatooine.

There is something deeply pleasing about revisiting the 1977 version — before the CGI accretions, before the franchise industrial complex metastasised into a content vertical, when it was just slightly wonky world-building, questionable haircuts and a desert that genuinely looked like it might ruin your moisturiser.

Watching it now, you can see how much of modern storytelling muscle memory it created. The pacing is almost quaint. The practical effects hold up alarmingly well. And the optimism — that scrappy, analogue rebellion energy — feels oddly refreshing in an era of algorithmically optimised content engineered to perform well in A/B testing.

It also turns out that once you know you’re going somewhere that lent its name to Tatooine, every sand dune becomes a scouting exercise.

I cannot promise I won’t hum the theme tune the entire time.

Travel

On Thursday, we’re heading to Tunisia for the first time.

Roman ruins. Star Wars geography. Sahara edges. North African food that I suspect will permanently recalibrate my spice tolerance.

It’s a short trip, so this week is all anticipation. Next week: sand, ruins, and (inevitably) reflections.

If you’ve got Tunis tips, send them quickly. Binary sunsets pending.

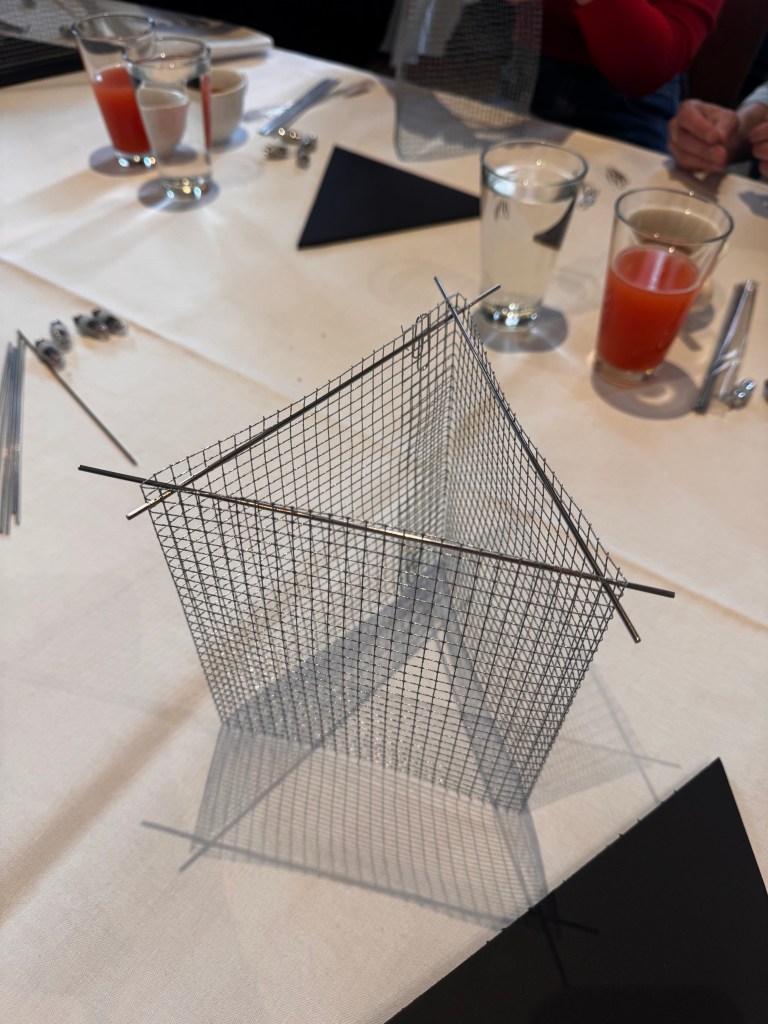

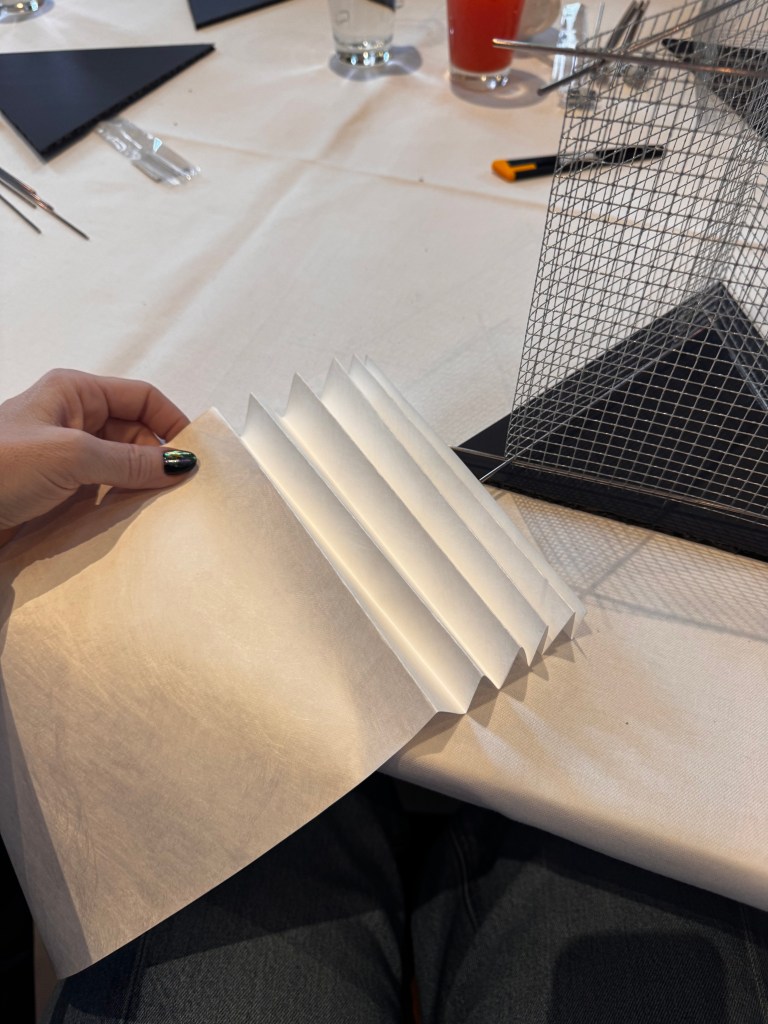

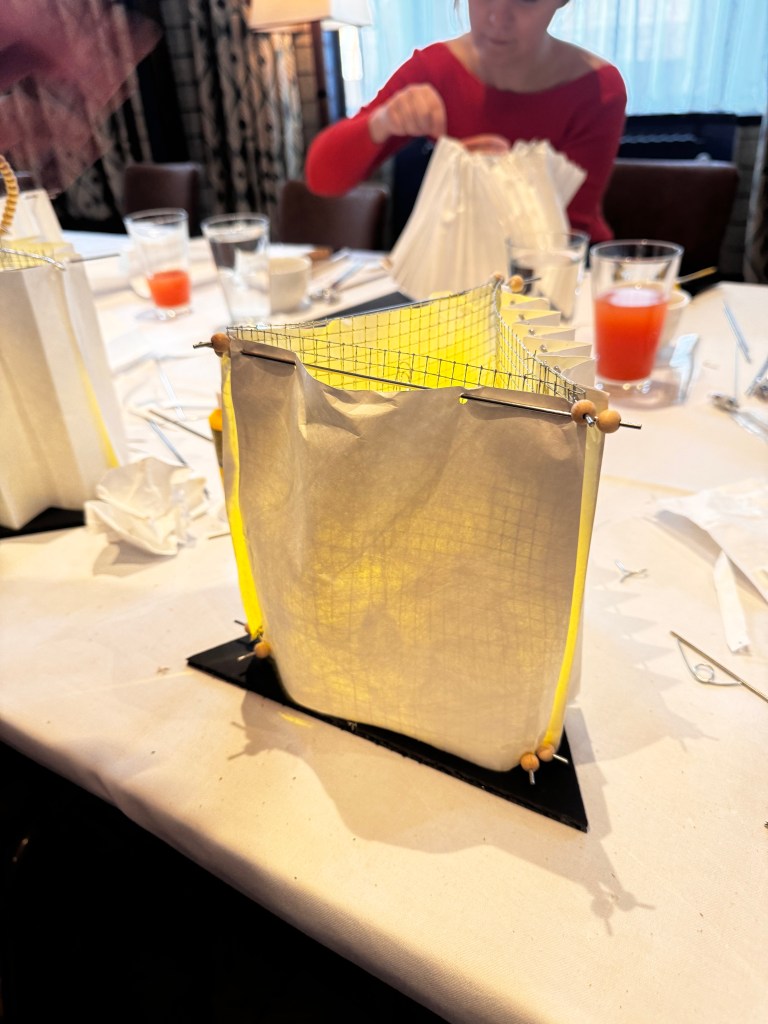

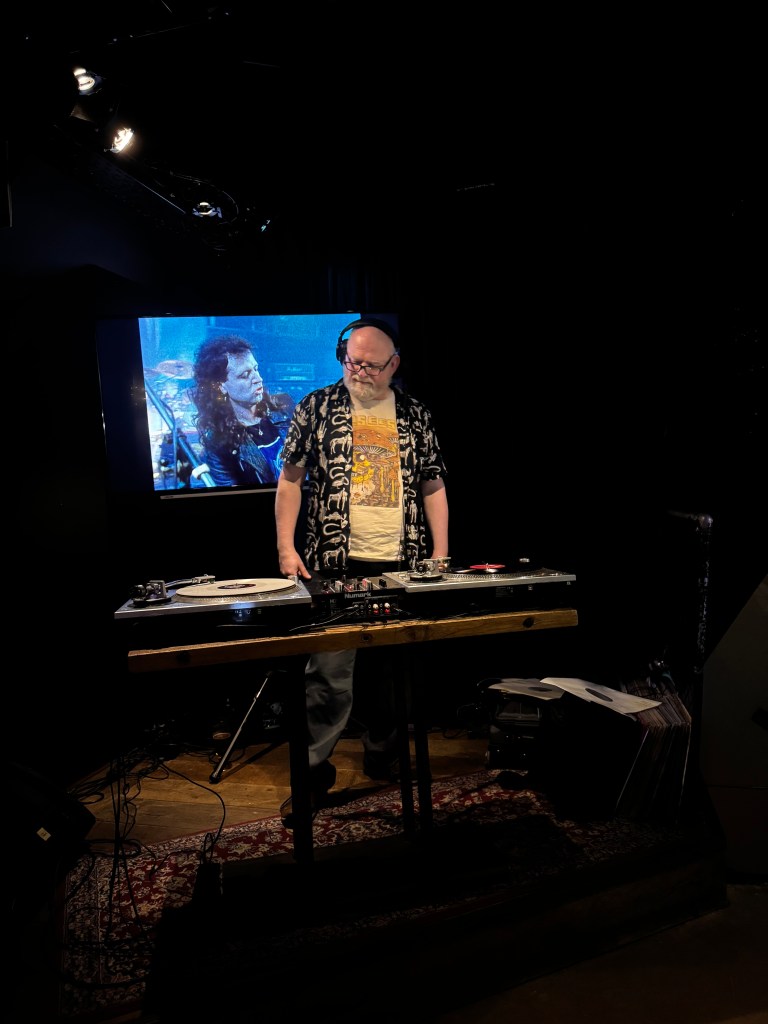

This week in photos