Twitter today responded to calls to make it easier for people to report abusive messages received through its service, pledging to introduce a ‘report abuse’ button.

This follows a weekend of controversy for the platform as feminist campaigner Caroline Criado-Perez faced a deluge of hundreds of vile tweets, including threats to rape and kill her, after she successfully campaigned for a woman’s picture to be put on a new banknote.

Criado-Perez refused to be silenced and took to both traditional and digital media to name and shame those who’d made the threats. Twitter drew criticism from politicians on all sides. Shadow Home Secretary Yvette Cooper described their response as “weak” and “inadequate”, while the Police’s social media lead called for the company to make further changes to the platform to prevent abuse.

In the past three days, over 50,000 people have signed the petition calling for the introduction of a ‘report abuse’ button. These tens of thousands will no doubt be pleased to hear Twitter has heeded their demands, and included this functionality in the latest release of their iPhone app, with other apps and sites to follow.

But we should be careful what we wish for. A button will not, alone, rid Twitter (or the wider world) of mysogyny and abuse. These are complex issues that will take more than a button to resolve. But ‘report abuse’ buttons have been known to be widely abused on other networks, an introducing this to Twitter will create new and complex problems for individuals and brands online.

Abuse buttons are easily abused

Back in 2010 I wrote about the case of a magazine which disapppeared from Facebook after falling victim to misuse of the report button. They found their page – and the personal accounts of all the admins – disappeared overnight, with no recourse to appeal.

After writing that piece, I heard similar stories from social media specialists of pages shut down and valuable content lost through malicious reporting, commercial rivalry, or simply mischief-making. Community managers and social media managers have found disappearing content to be a depressingly regular occurrence. It only takes a handful of reports to have content removed automatically – putting campaigns and content at risk of malicious removal, and putting the personal accounts of the admins at risk of deletion.

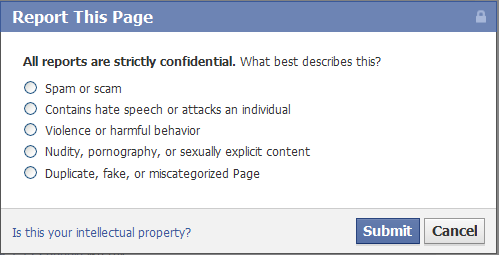

Facebook has long since made it simple to report different kinds of abuse, from breaches of terms of service to copyright violation, but provides no means by which brands and organisations can appeal when this is misused.

More recently Facebook introduced the concept of ‘protected accounts’, where pages are protected from automatic shut-down – but this isn’t a service they publicise, and is largely only available to paying advertisers.

Introduction of a similar mechanism on Twitter ironically creates a whole new means by which trolls can abuse those they disagree with. The report abuse button could be used to silence campaigners, like Criado-Perez, by taking advantage of the automatic blocking and account closure such a feature typically offers. In that way, it could end up putting greater power in the trolls’ hands.

A report feature could also be used by campaign groups to ‘bring down’ brands or high-profile individuals (such as MPs) through co-ordinated mass reporting.

The abuse button will do little to prevent abusive messages

It’s not at all clear that an abuse button will do much to prevent the use of abusive and threatening language on Twitter, either.

Unlike Facebook – which these days makes it quite difficult to register a new account, and in storing so much of your life history creates implicit incentives toward good behaviour as users truly fear having accounts deleted – the barriers to entry on Twitter are low. All you need to create a Twitter account is an email address; you can be up and running in under a minute. If users are blocked or banned for abuse, they can – and will – simply create new IDs and keep on going.

The introduction of a report button could simply create a tedious game of cat and mouse in which the immature and misogynistic simply treat being reported and banned as a wind-up to be ignored.

Button-pushing mechanisms rarely create real change

To create real change, and really tackle the issue of abuse on Twitter (and indeed, mysogyny in the wider world) we have to recognise it’s s complex problem which can’t be resolved by giving people a button to press and make it go away.

Abuse is sometimes clear-cut, but often it’s subjective. What someone may regard as a joke or sarcasm, others could see as abuse and threatening language – as the Twitter Joke Trial proved all too well.

Threats of violence and rape are, rightly, against the law (the Malicious Communications Act 2003 outlaws electronic communications which are “grossly offensive” or threatening). Writing for the Guardian, feminist writer Jane Rae argues more could be achieved by applying these existing laws.

It’s encouraging to see the UK police have already made one arrest over the threats against Criado-Perez, because seeing people being prosecuted for what is a serious crime sends a far stronger message to trolls than having their Twitter account blocked. I, for one, hope the police take action against more of those who have threatened violence.

A report button is an ineffectual knee-jerk response to the issue. But that it’s been introduced in a hurry – leaving no time to ensure it’s properly thought through, resourced, or supported by processes created through discussion with law enforcement agencies – means this is a move that’s likely to do little to tackle abuse on Twitter, but rather create new ways for people and brands to be abused.

UPDATE: Several bloggers have expressed reservations about this too, thinking more about some of the problems with trying to automate the process of identifying and tackling abuse. Here are some posts worth reading:

- Martin Belam: This isn’t a technology problem. This is a misogyny problem.

- Tom Phillips: Twitter abuse and magic wands

- Mary Hamilton: Twitter’s freedom of speech

- PME2013: Trolls and the Twitter boycott

- Brooke Magnanti: Feminists boycotting Twitter is not the way to end trolling (Telegraph online)