Today is the shortest day of the year. Winter’s nadir. The moment the light turns back in the right direction, however grudgingly.

I find winter utterly miserable at the best of times, and this year more so for having skipped the opening act by being in Japan, only to return and take the full European version in one concentrated hit. It’s faintly reassuring to know that, technically, things improve from here, even if January and February — the grimmest months — are still very much ahead.

Still, direction matters. And as it happens, this week has been full of looking back at moments that felt bleak, uncertain, or poorly timed at the time — and recognising them, with the benefit of distance, as the point at which things quietly started to turn.

From here on in, it gets brighter.

This week at work

We kicked off a new project with a new client, which is always a small thrill. We have a fairly standard approach to kick-off meetings — getting clear, early, on who actually needs to be involved, what we’re trying to achieve at a high level, realistic timelines, and the immediate next steps that stop everything dissolving into “we’ll come back to that”.

What’s exciting about this one is the ambition. The brief talks openly about building an AI-ready — even AI-first — communications infrastructure. But crucially, there’s a shared recognition that none of that will be achieved by simply bolting on new tech and hoping for the best. Instead, the foundations are the unglamorous but essential things: well-managed content, clarity on roles and responsibilities, and governance that enables rather than constrains. Get those right, and you create the conditions for a genuinely flexible, hyper-personalised channel ecosystem — one that adapts to people’s needs, preferences and ways of working, rather than forcing everyone through the same narrow funnel.

I’m already very excited about making this real. Proof, if any were needed, that I am a massive nerd.

Less exciting: the inevitable end-of-year admin scrum. Last-minute requests, frantic emails, and invoicing going right down to the wire. Very much the yin to the project work’s yang.

And while we submitted the final three chapters of the book last week, this week marked the start of the second review pass — looping back to the opening chapters to tidy, tighten and make sure the full narrative holds together as a coherent whole. Less triumphant finish line, more careful stitching. Which, in many ways, feels about right.

Also this week

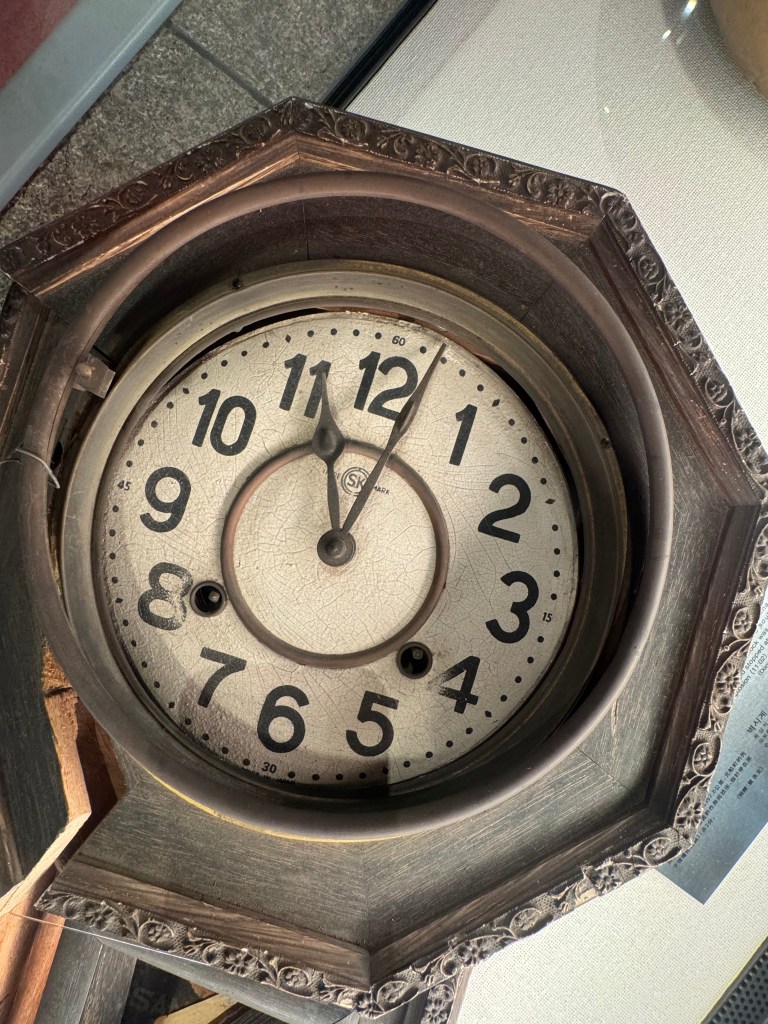

It marked ten years since I left my job, with nothing to go to, a few days before Christmas. At the time it felt reckless, frightening, oddly calm — and also inevitable. The kind of decision that only makes sense once it’s already been made.

It felt like the right moment to reflect properly on what happened, how it felt then, and what’s unfolded since. So I wrote a short series of three blog posts: not a triumphalist origin story, but a more honest account of discomfort, drift, relief, uncertainty — and the slow accumulation of orientation rather than any single turning point.

Here’s the three posts

- The Break covers the decision to leave

- The Long Middle looks at the aftermath, and the years of working out where to go next

- Orientation, Not Arrival covers how I look at things now

The response has been… a lot. The comments have been generous, but it’s the DMs that have really been on fire. So many women saying how closely it mirrors their own experiences: the erosion of confidence, the sense of being managed out rather than supported, the quiet calculation that leaving might be less costly than staying.

On the one hand, it’s reassuring to know I’m not alone. On the other, it’s deeply depressing that this pattern is so common — and that so many talented, experienced women end up circulating through the freelance market not out of burning entrepreneurial ambition, but because organisations make it structurally and culturally difficult for them to remain. Not a talent pipeline so much as a slow leak.

In London this week, I went to the annual Christmas Carol fundraiser for The Food Chain — a small but vital charity providing nutritional support to people living with HIV. The charity was formed in 1988 by a group of friends who simply delivered Christmas dinner to people living with HIV, who faced stigma and loneliness as well as as the illness.

The service struck a thoughtful balance: a lovely choir, extremely enthusiastic singing from me and friends, a genuinely funny speech from Jay Rayner (the charity’s patron), and a more sombre one from the CEO on why this work still matters — even now, when HIV is clinically manageable but inequality, isolation and food insecurity remain.

Somewhere between the carols, the message about feeding the hungry, and the sheer warmth of it all, it finally put me in a Christmas mood.

Consuming

📺 Watching

In what has now become an annual tradition, I hosted my Feminist Film Club. The format is simple: we re-watch a classic film and drink whenever we spot an instance of problematic behaviour. It is, as methodologies go, robust.

Previous years have seen us reassess Love Actually through a feminist lens (spectacularly problematic; blind drunk) and Pretty Woman (surprisingly progressive; mild surprise all round).

This year, we tackled Dirty Dancing. And to my surprise holds up remarkably well. Bodily autonomy. Class politics. A woman allowed to want things, choose things, and not be punished for it. A quietly feminist film hiding inside a watermelon-based cultural memory.

We still got drunk, obviously — it was the weekend before Christmas. But it was a genuinely lovely girls’ night in, equal parts cultural critique and joyful nostalgia.

Connections

Also in London, I caught up with fintech OGs Sarah Kocianski and Harriet Allner for lunch and the traditional end-of-year ritual of putting the world to rights.

Coverage

My latest piece appeared in Reworked this week. This month’s editorial theme — next-generation self-service — finally gave me the excuse to write something that’s been brewing ever since I first came across Jamie Bartlett’s idea of “techno-admin”.

The piece isn’t really about self-service so much as the quiet redistribution of administrative work onto employees. Technology doesn’t remove the work; it just relocates it — updating records, fixing errors, navigating opaque systems — all framed as empowerment, and rarely acknowledged as labour.

I argue that genuinely next-generation self-service should reduce admin rather than disguise it, designing around human reality instead of system convenience.

Travel

My trip to London marked my last trip of the year. According to Flighty, that makes 59 flights in 2025 — which is bad, even by my standards. A frankly unhinged amount of time spent hurtling through the sky, drinking tiny cups of bad coffee and being a #LoungeWanker.

But here’s the strange bit: for the first time in… I don’t know, a couple of years? I have no travel booked. Nothing pencilled in. No flights lurking ominously in January.

It feels deeply unnatural. Like I’ll wake up like the mum in Home Alone with the sudden realisation I’ve forgotten something important.

Until then, I’ll enjoy being gezellig at home with my favourite people. Merry Christmas, Fijne Feestdagen to you and yours.

This week in photos