Eve Shuttleworth proposed this session in response to a question that arose earlier in the day: Where is journalism heading, and how do press offices need to change in response?

The web professionals session I went to earlier touched on the same issue – how do we develop the skills we need within our web and communications teams to respond to changing media demands?

Journalism has changed enormously over the past decade or so. News organisations large and small have woken up to the web, and are developing a wider range of rich media content. Local papers as well as national ones are using audio, video and interactive graphics to enhance their stories.

This has led to a huge cultural shift in news, with print and web journalists being located together and badged as content producers. The overwhelming feeling in this session was that communicators need to adapt in a similar way.

Press officers can’t focus solely on writing and selling-in written press releases; we need to take a broader approach to content, producing material for the corporate website as well as complete asset packages for the media to use.

Several of the group gave examples of journalists accepting their video content, although there’s a clear divide between the specialist and local press and the big boys on the nationals.

Major national news organisations are reluctant to take video material from the government (and rightly so in my view). But local and regional press are poorly resourced and more inclined to accept PR material.

Someone asked: the budget-slashing job cuts and subsequent culture of ‘churnalism’ that one sees in much of the regional press is beginning to creep into the national press too, in response to the poor advertising market and declining sales. Does that mean even major news organisations will start accepting complete packages from us too?

There was deep unease about this from much of the group; while an under-resourced press makes PRs life easier, it’s not exactly indicative of a free press performing its fourth estate function of holding government to account.

Many of us said we’re troubled by the lack of critical analysis press releases get. All too often, journalists will take a press release, find any contrary opinion, and present this as reasoned analysis. This over-simplification of debate does neither communciator nor journalist credit; it’s rare that there are two sides to every story. Usually there are at least three or four, and sometimes there really is just one.

This isn’t the fault of journalists, but of proprietors who have cut editorial teams, merged titles and slashed budgets so there simply isn’t enough journalistic resources to get out and report the news. One press officer said “make life easier for journalists and they’ll bite your hand off”.

Sarah Lay gave a great example of how they did this during the local elections in Derbyshire. Making a wide range of material available to journalists online meant that they recieved more coverage than they’d normally expect, yet had to take fewer calls from journalists. That’s a win-win for everyone (especially Sarah and her team, who took home a PR Pride award for this).

89% of journalists are using blogs and social media to research their stories, and it follows that the public sector need to engage with these too. Communciations teams need to keep an eye on blogs, Facebook, etc so problems can be identified and dealt with early before they become more reputationally damaging.

Alastair Smith explainined how Newcastle City Council managed a story which sprung up on Facebook. By responding to the group and offering to meet and talk about their concerns, they managed to turn what was a negative story into a positive one that helped the campaign group get what they wanted.

Communications teams just aren’t set up to respond to social media. Reporting lines for press releases usually require signoff from senior staff and politicans, a process which can take days – a timescale incompatable with the demands of social media.

Neil Franklin told us how he used to manage the Twitter feed at Downing Street, arguing that communicators need to be realistic about responding in a timely manner.

I suggested we borrow the concept of ‘presumed competence’ used by the Foreign Office. Back when an ambassador was sent to Ouagadougou and not heard from for months at a time, their masters back home had to assume they were capable of getting on with it. Social media has the same disconnect between local demands and ability to get sign-off from the centre. We may find it easier to respond to social media if we have a set of agreed ‘lines to take’ that we trust our teams to deliver, and refer upwards only by exception.

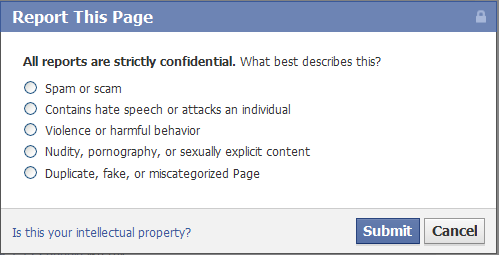

Whatever you chosen approach, organisations need to develop a policy for dealing with social media comment. Michael Grimes adapted the well-known US army model into this very useful process model for dealing with social media comment.

Others said it was difficult and unhelpful to have two different approaches to responding: It’s just media, and media is social. We need to have a vision for content generally, and plan our resources accordingly.

Someone added that we need to think about tone, and “don’t treat citizens as journalists”. While it’s true we speak differently to journalists as customers, the rise of the citizen journalist – and initiatives like Talk About Local – mean the distinction between the two is blurring.

Someone talked about this Clay Shirky article, which argues “we will always need journalism, but we won’t have journalists”. The fourth estate is vital in a democratic system, so if we’re seeing less meaningful analysis of our work by the traditional media, then we should welcome it from non-traditional sources.

Online journalists, of the traditional as well as citizen variety, are becoming as much curators of content as creators, aggregating content from the wider web and bringing it to the attention of their networks. Communications teams should try and emulate this in what they produce, for instance by linking to related articles or useful background information.

Eve Shuttleworth said the Ministry of Justice is starting to monitor blogs and social media to get a feel for what the issues are, but has not yet made the decision to respond. One of the issues they’re grappling with is whether press officers should respond as the organisation, or as themselves.

Identifying individuals could have security implications, especially where issues are controversial.

All of this points to an urgent need to reassess the service we provide. We need to develop a vision for how we provide content, and ensure we can resource this in a way that meets the media’s diverse and changing needs, the needs of the audience and those of the organisation.