This week was spent under Tokyo’s pulsating screens, where the pavements hum, the escalators chirp, the traffic lights sing, and you’re permanently one missed step away from being swept into a tide of humanity. The city doesn’t so much greet you as flip your settings to 11 and leave you buzzing like a faulty transformer.

If you’ve never experienced it, it’s hard to explain the sheer scale of the sensory assault. It’s immediate and total. Visually, the city is a chrome-and-neon deluge: vast video boards loop hyper-real animations that bathe the crowds in shifting washes of cerise, cobalt and electric green. Every surface is broadcasting something — a brand, a warning, an offer, a jingle — all competing for your attention at once.

The soundscape is its own kind of madness: pachinko parlours spilling manic 8-bit cheer into the street; “don-don-donki Don Quijote” worming its way into your skull; the rhythmic clatter of the Yamanote line overhead; clipped, polite announcements issuing instructions you’re too overloaded to follow; the constant shuffle and thrum of tens of thousands of footsteps. It’s a multi-layered wall of noise you feel as much as hear.

Even the air has texture: a metallic tang of exhaust, the savoury steam of yakitori stalls, the strangely comforting detergent-clean fragrance that leaks from department stores every time their doors sigh open.

It’s an unrelenting, high-definition reality that demands attention. Your brain simply cannot keep up with the bits-per-second being hurled at it. You become both anonymous and hyper-stimulated. You’re a single vibrating nerve ending plugged into a city-sized nervous system.

As a dyed-in-the-wool city girl, I was both in love with it and completely exhausted by it. Exhilarated one minute, brain-fried the next.

But every night, as my circuits started to smoke, I slipped back to Shimokitazawa: a low-rise pocket of sanity I’ve stayed in so often it feels like popping on a familiar jumper. Gentrified? Absolutely. But still human-sized, warm, and (crucially) horizontal. After a month in slow, sloping Nagasaki, Shimo was the space I needed to transition into Tokyo without short-circuiting entirely.

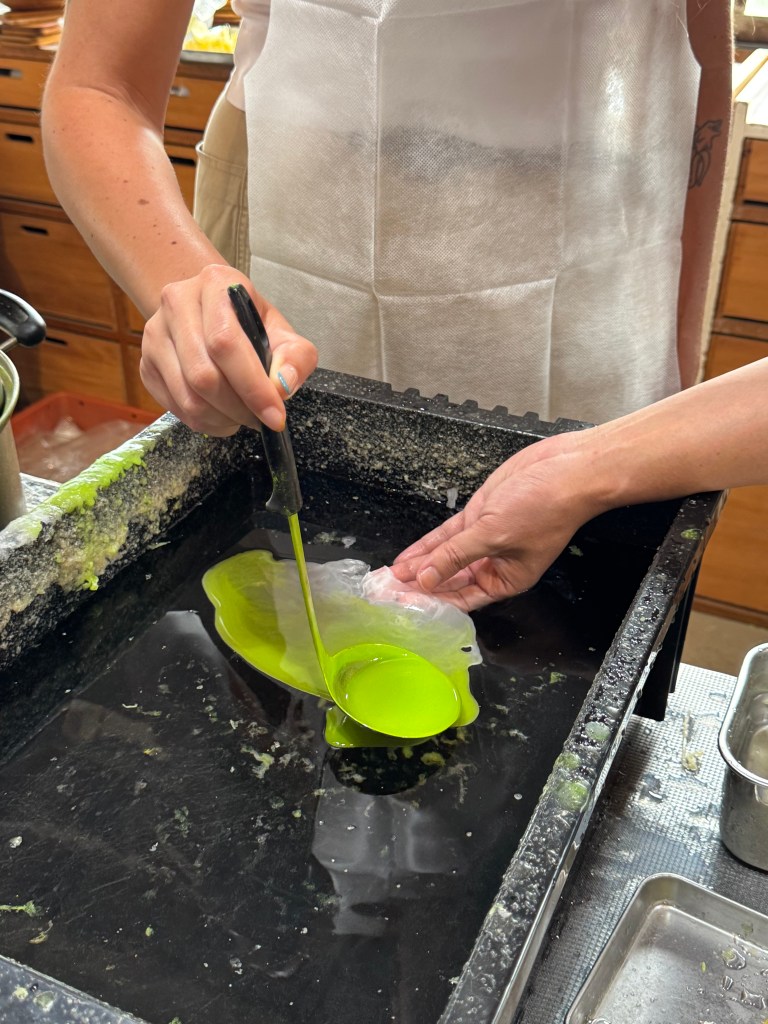

Evenings in Shimo were the antidote to Tokyo’s intensity: smoky teppanyaki counters frying okonomiyaki bigger than your face; tiny wood-panelled izakayas with fogged-up windows; a six-seat local bar where the drinks are strong, the welcome quiet, and the conversation optional. In a city that overwhelms by design, Shimo made the whole thing survivable.

The rest of the week unfolded as a tour of contrasts — human, urban, sensory and technological. The kind of juxtapositions Japan does with unnerving ease.

I went to two gigs: one in Shimokitazawa, one in a suburban burger restaurant, both showcasing that deeply Tokyo magic trick of creating tiny, intimate worlds inside the sprawl. There’s a particular joy in finding these pockets where no one cares that you’re foreign; you’re just another person there for the music.

I finally made it to the Yayoi Kusama Museum (worth the booking hassle, worth the hype, worth the wait). I wandered through Tokyo’s parks in full autumn drag, riotous maples showing off under cold blue skies. I slurped heroic amounts of ramen in small rooms filled with smoke and laughter.

I made the pilgrimage to TeamLab Planets, something I’d avoided for years because on paper it is precisely the sort of place I should hate. Big Influencer Energy. The kind of venue where you fully expect to be elbowed aside by someone wielding a ring light like a weapon. I arrived ready to roll my eyes so hard I’d sprain something.

Wading through warm water in a mirrored room has no business being as good as it is. Nor does being surrounded by giant drifting flowers; on paper it’s pure gimmick, yet there I was, perilously close to having feelings. It’s sensory overwhelm with actual depth: playful, deliberate, and mercifully not designed solely for people who say “content creator” with a straight face.

I also did something rather lovely: a walking tour of Tokyo with a palm-sized robot perched on my shoulder, remotely operated by someone with a disability, working remotely from elsewhere in Japan. Fun, surprisingly polished, and a little glimpse into a future of work I’ll write much more about another time.

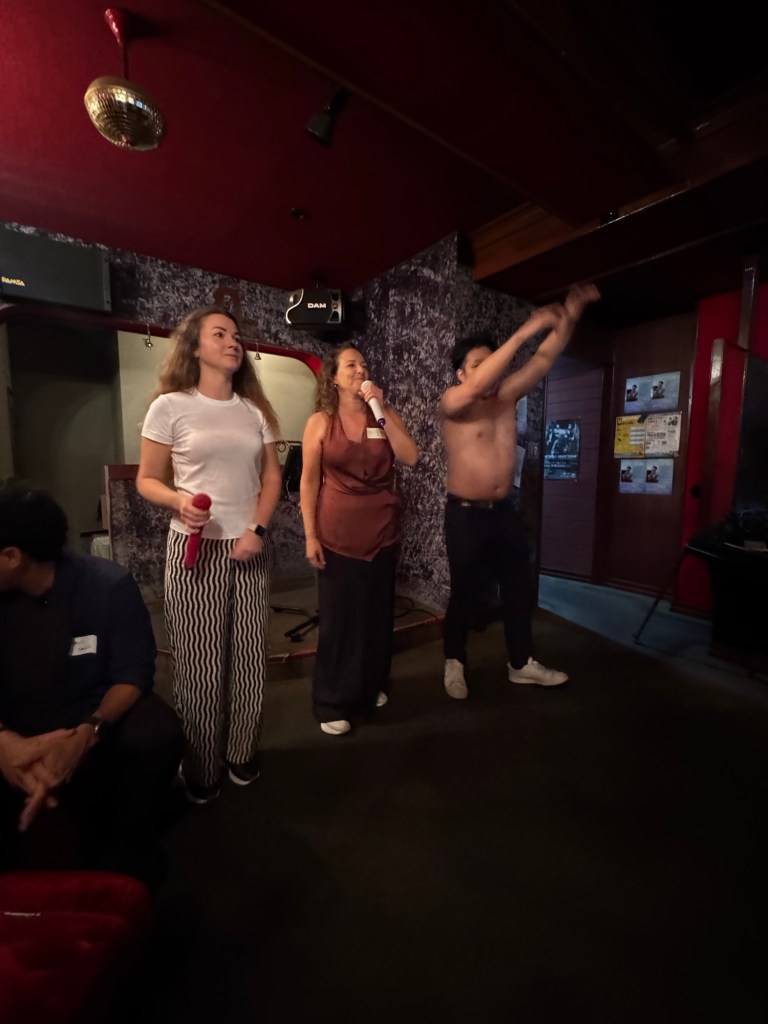

And then there was Kagaya. I genuinely don’t know how to describe Kagaya Izakaya without sounding unhinged. It’s nominally a dinner, but in reality: a one-man piece of performance art that veers between slapstick, surrealism and something approaching group therapy. At various points there were puppets. There were costume changes. There were props I’m fairly sure violated several fire codes. The man has the timing of a seasoned comedian and the energy of someone who’s drunk six cans of Monster and made peace with chaos.

The food was excellent, but also completely beside the point. If David Lynch ever opened a pub, it would be this: unsettling, hilarious, oddly tender, and impossible to explain to anyone who wasn’t in the room. I’m still trying to process it tbh.

He asked that we don’t put videos on the internet, and I absolutely respect that. Some experiences deserve to stay unmediated, uncaptured, held in the moment rather than flattened for the feed. Kagaya is very much one of those. So this one solitary snap it is.

Amid all this, I published my first reflection from Nagasaki: an article for Reworked on what organisations can learn from the digital nomad movement. It’s the first of what will no doubt be many pieces. Now that I’m briefly still, I finally have space to breathe, process, reflect and write. This whole experience has given me a lot to think about; I’ve barely begun to scratch the surface.

I also made a reel summing up my month — forty-odd one-second clips stitched into a fever dream of trains, temples, islands and neon. The algorithm seems determined to bully me into becoming better at video, so… apparently that’s a 2026 project.

Between it all: the shopping. So much shopping. Tokyo retail isn’t an activity; it’s an endurance sport. One minute you pop into Don Quijote “just to have a look”, and two hours later you’re on floor 5 of 8, dehydrated, overstimulated and clutching two baskets filled with matcha KitKats, face masks, Totoro purses, Super Mario bag charms, Ichiran ramen kits and a hair towel you saw on TikTok. You’re seriously considering upgrading to one of those little basket trolleys so you can start a third.

You have lost all sense of time. You have no idea if the sun is still up. The shop jingle has played for the 756th time and permanently lodged itself in your skull. Every surface flashes something at you; every aisle whispers “buy me.” You are borderline delirious. You reach — helplessly, inevitably — for another Hello Kitty coin purse. Bic Camera, Yodobashi Camera, Donki… they’re all the same fever dream: capitalism at its most chaotic, joyful and unhinged.

And then — abruptly — Amsterdam.

Back home, I battled the jetlag and stayed awake long enough to see The Hives at AFAS — a band I’ve been going to see for over two decades. I’ve seen them in a tiny venue in Malmö, a community centre in Warsaw, a big corporate venue in London, and everything in between. Pure, chaotic rock-and-roll energy that hasn’t dimmed a watt in 20 years.

And honestly, after six weeks in Japan, stepping out into the Dutch winter (a hard, unfriendly zero degrees) and trying to remember how to be a person in my own life again… that helped. A reminder that some rhythms — loud guitars, shared joy, a band giving absolutely everything — travel with you.

And that’s it. My final weeknote from Japan.

Six weeks that shifted how I think about work, community, belonging and pace. A reminder that cities are laboratories, that culture is generous, that work has a future if we’re imaginative enough, and that slowing down long enough to notice is half the point.

Not quite the end of the story, I suspect. But definitely the end of this chapter.

This week in photos