The Twitter rape threat row shows no signs of abating, as many users pledge to take a one-day break from the site this Sunday, August 4th. Author and columnist Caitlin Moran says she’s taking a 24-hour ‘trolliday’ from the site “because it will focus minds at Twitter to come up with their own solution to the abuses of their private company”.

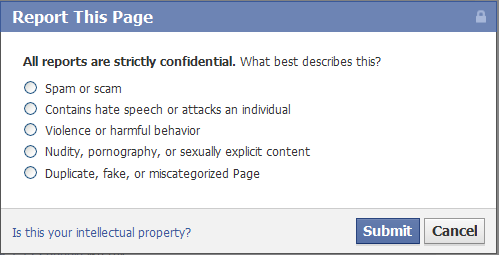

Twitter have already caved in to demands for a ‘report abuse’ button – which, as I argued earlier this week, is likely to cause as many problems as it solves. But many commentators claim this doesn’t go far enough, and are calling for an end to anonymous accounts on social network sites like Twitter.

Writing in the Guardian, Simon Jenkins claims that the internet has become a masked ball, “whose concealed dancers may be corporations or governments, paedophiles or rapists, weirdos or fools”, demanding that “it must be regulated”.

Jenkins echoes the online disinhibition effect, “a loosening (or complete abandonment) of social restrictions and inhibitions that would otherwise be present in normal face-to-face interaction during interactions with others on the Internet”. Anonymity, it’s suggested, is itself the cause of so much anti-social behaviour online.

Although I would certainly never condone the type of abuse that Moran describes, we need to be wary of losing the enormous benefits that anonymity on the web brings all of us.

Anonymity can be a wonderful thing. Many of those commenting on blogs and forums are doing so from beneath a pseudonym, so they can speak freely on the issues that concern them without it being part of their Google footprint, drawing scorn from real-life friends and family.

Anonymity allows us to practice having different points of view; we can be a more conservative or liberal version of ourselves in online discussions, which helps us to form our own opinions and arguments.

And it’s there where the spectrum of trolling begins. At one end you have someone taking a contrary opinion in order to get a rise out of someone. This kind of anonymous trolling can be a noble art, and we saw a fine example of such this week, when Pukkah Punjabi trolled the ‘racist van’.

At the other end of the spectrum you have people shouting vile abuse at strangers. This is clearly wrong, and rightly illegal. What one woman might be willing to ignore, or consider a joke, another might find scary and threatening, especially when received as frequently as some high-profile women do.

Where trolling ends and abuse begins is difficult to define, but we should exercise caution so we don’t lose the benefits of anonymity in our rush to rid the web of abuse.

MIT academic Sherry Turkle has written extensively about the value of the anonymous web in allowing people to experiment with different facets of their personality and opinions, in order to develop our sense of self and identity. In Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet, Turkle talks about how the internet allows us to engage in new ways of thinking about evolution, relationships, politics, sex, and the self.

As an example, someone who is coming to terms with their sexuality might participate in online discussions in LGBT forums. Being able to do so without risk of disapproval from friends or families can prove a vital lifeline for a young person to develop their identity and sexuality.

Anonymity can bring benefits in everyday situations. For example, when I was last looking for advice on finding a new job, I was much more comfortable doing so in the knowledge that my boss at the time couldn’t look it up.

But anonymity can equally be an issue of personal safety. I have one friend who will only comment online under a pseudonym as they have been a victim of real-life stalking.

For others, anonymity is a matter of life and death. Twitter is widely thought to have played a key role in galvanising the Arab Spring, but that was only possible because people felt they could use it anonymously, without fear of reprisals. We should be very mindful of the implications of ending web anonymity in those parts of the world where speaking publicly can have serious consequences.

Padraig Reidy, blogging in response to Caitlin Moran, hit the nail squarely on the head:

“The web is wonderful, and possibly the greatest manifestation of the free speech space we’ve ever had, but it’s also susceptible to control. Governments such as those in China and Iran spend massive resources on controlling the web, and do quite a good job of it. Other states simply slow the connection, making the web a frustrating rather than liberating experience. Some governments simply pull the plug. The whole of YouTube has been blocked in Pakistan for almost a year now, because something had to be done about blasphemous videos.”

The web is far less anonymous than it used to be. When I first started using it, everyone was anonymous, all the time. Then, as now, there were a handful of idiots who would abuse that anonymity in order to get attention.

In the two decades since, the web has opened up communication and ideas in ways few dreamed possible. As a tool which enables people to speak freely with others all over the world, putting thousands of information sources at our fingertips, the web has fueled revolutions and overthrown governments. But through providing anonymity, it’s also been revolutionary for individuals, allowing people to discover their sense of self, to find a partner, to form and change opinions, and much else besides.

While more can be done to streamline the process of reporting and preventing abuse, we should all be very wary of losing the real and valuable benefits anonymity can bring in a knee-jerk reaction to a small but vocal group of idiots.

(Photo credit: Stian Eikeland on Flickr)