The week or so since our last post has seen some major names move toward a remote-first future. Mastercard announced it expects staff to work at home until there is a vaccine, while Facebook shared their plans to shift around 50% of staff to permanent remote work.

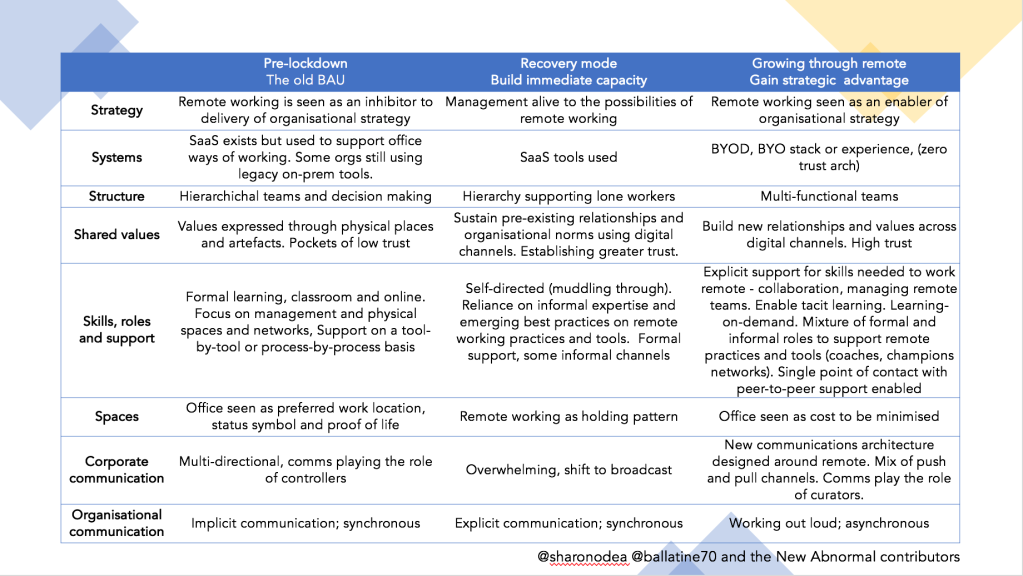

With the landscape moving so quickly, Matt and I spent some time last week working through the remaining themes we identified as priorities for organisations that want to make remote an enabler of (rather than a barrier to) delivery of their strategy.

In our first post we looked at systems, structure, shared values, skills and roles and strategy. Take a look.

Now we turn to the final four themes

Spaces

For a long time, offices – like factories before them – where were you accessed the equipment necessary to get work done. The availability of cheap laptops and ubiquitous broadband means this hasn’t been the case for at least a decade.

Nonetheless, offices continued to be the primary place of work because of their secondary purpose; the belief that bringing people together in the same place helped to foster collaborative working. Rows of open plan desks gave way to mixed environments offering impromptu meeting spaces to facilitate this. Even the most digital of companies such as Google and Facebook continued to encourage employees to come to the office in order to foster innovation.

Covid changed all of that, forcing all to figure out how we can work individually from home. In the past 10 weeks we’ve used collaboration tools to try re-create the in-person interactions we had while working in the physical office.

Spaces are now sitting empty, and people are wondering what we do with them next. There’s an assumption that we’ll continue to work at home for individual tasks, with offices being re-configured for more collaborative in-person working such as workshops once this is all over.

However, early indications suggest that assumption could be some way off the mark. Social distancing rules dictate that even where offices are being re-opened, meeting rooms and breakout areas need to stay out of bounds. A room that could have hosted ten is now strictly capped at two. How do you manage a group brainstorm around the whiteboard while keeping everyone two metres apart?

You don’t. You need to do what Matt and I did for this session and find ways to do this online.

(We used Miro, a tool we’ve both become evangelical about in recent weeks, because it allows you to do things collaboratively with people in a way that you can’t do in physical space, focusing conversation yet making it possible to integrate other media. It’s what hypertext was supposed to be.)

People will need to learn how to use such tools for virtual collaboration. But putting collaborative tools into the hands of every employee democratises them and, in turn, drives up the quality of collaboration. Especially when compared with scarce physical tools such as interactive meeting room whiteboards.

And once these skills and habits have been gained, it leaves open the question of what physical workplaces are actually for.

But physical spaces serve other purposes. These include:

- Access to specialist equipment: clearly a research scientist is not going to set up a complete lab in their spare bedroom

- Status symbols: those big glass towers making up some of the world’s most expensive real estate in New York, London and Hong Kong send a clear message about your brand and stability

- Proof of life: for smaller companies, a physical office is considered evidence you exist, helping to build trust with customers

- Grounding in the community: this is especially true for local businesses, public/voluntary sector organisations or those with a longstanding connection with place

Additionally, there will always be some people who can’t – or don’t want to – work from home. For example someone living in crowded accommodation with children at home.

So organisations shift to remote or distributed work, their use of physical space will change but not disappear. The focus will move to supporting smaller numbers of staff with specific needs for office space, and those secondary purposes listed above. Office space – and the roles supporting it – becomes a cost to be minimised.

This has some potentially huge second-order effects for property markets and for cities. WeWork’s business model looks even more precarious than it was, as corporate tenants retrench from secondary spaces on short leases to their owned properties. At the same time, we could see the rise of local co-working hubs providing office space for those who need it without the long (and in these socially-distanced times, potentially dangerous) commute. The Irish community organisation Grow Remote provides a useful model here; they champion physical and virtual hubs to those working remotely diverse organisations benefit from connection with one another and with the communities in which they’re based.

One outstanding question is what, if anything, replaces the function of the building as a signal of prestige. What’s the digital equivalent of the client floor or the tower projecting its logo across Hong Kong’s harbour?

Corporate communications

Organisations and their leadership need to communicate to their people about their goals, values and progress. They want to align employee action with their purpose and objectives, and keep people engaged and informed.

In the past couple of decades the internal communications profession has moved away from a top-down distribution role to one of curator, controller and advisor. They understand what is going on in the organisation at all levels, ensuring that employees are in the loop, and facilitate two-way conversation between employees and leadership.

Covid has forced corporate communications into crisis mode. The priority has been to keep people informed about what their employers are doing to keep them safe, keep customers happy, keep people in work and ensure the business stays solvent. And at the same time, many of the most effective tools in the communicators’ armoury aren’t available, like the old-fashioned poster and digital signage.

The result has been an overwhelming shift to broadcast channels. In a straw poll during my keynote at last week’s Brussels Digital Workplace Event, 87% of attendees said they had relied especially on email and 82% on a traditional intranet to keep employees in the loop. But at the same time, organisations have had to more actively listen to what employees, using things like sentiment analysis.

As organisations shift to this New Abnormal, corporate communications can’t simply go back to what they were doing pre-Covid. Instead, they need to redesign their channel architecture and content strategy around the needs of employees who rarely come into the office.

That means:

- Understanding employees’ need for communication, and taking a user needs focused approach to designing and delivering it

- Offering a mix of push and pull channels, so people receive the information they need, but also have the means to find what they want and be confident it’s accurate

- Finding ways to cut though the (now somewhat overwhelming) noise and ensure what people get is relevant and timely. This could mean borrowing techniques from digital marketing and using data to target employees effectively. But equally, it could mean looking at how messages naturally propagate within organisations – via the grapevine – and hacking that.

- Finding the right balance between listening to employees and understanding what they want, without surveiling them

Getting this balance right means relying less on copying best practices, and rather on understanding employee needs, experimenting with new approaches, and seeing what gets cut through. All of that requires a more robust approach to measurement.

Organisational communication

Related to this – and often using the same channels – is how people within organisations communicate with one another to get work done.

In a physically co-located team, communication is implicit. That is, you pick up on conversations happening around you. You can lean over the desk and say “Hey, Dave, are you working on this? Do you know where this file is? Can you tell me the latest on this customer?”. That communication is largely synchronous, in that it happens while you’re both in the room, and much of it is tacit; we communicate without even thinking about it, through our body language and tone.

In recovery mode we’re still working synchronously, but we’re having to work much harder to do that, and be more deliberate. But that’s exhausting. It also demands more of our energy and attention; Zoom fatigue is a very real phenomenon.

Making this work long term means retaining that explicit, deliberate communication, but adapting it to be less time-consuming and attention-demanding by embracing asynchronicity.

That means mixing up modes and channels, using interactive channels (like Miro) or collaborative documents, rather than video feeds.

Embracing asynchronous working has secondary benefits, too. It means more knowledge and conversation is committed to corporate memory, and allows people to work more flexibility across shifts or time zones.

To shift to asynchronous communication and collaboration in order to become truly remote-first, organisations need to give people training, coaching and time to experiment with a flexible suite of tools.

Support

Organisations offer support to employees to get their work done – from providing transactional services to troubleshooting issues and problems with equipment, facilities, software and so on.

Traditionally this is offered on a tool-by-tool or service-by-service basis, meaning the overall support landscape is as fractured and siloed as the organisation itself.

In a traditional workplace this is augmented by informal support. People will turn to a longer serving or otherwise helpful colleague to help them resolve problems.

Shifting to home work has left employees reliant on digital channels to get work done, but often struggling to access help to resolve problems or learn new systems, as colleague support is unavailable and helpdesks overwhelmed.

For organisations to turn remote work into a strategic advantage, they need a greater focus on supporting employees to be engaged and productive. They need to understand that employees are reliant on a complex and fragmented set of tools to get work done, and when these aren’t working employees are left frustrated and productive time is lost.

This means:

- Replacing fractured single-system help with a concierge approach focused on unblocking problems for the user quickly

- At the same time, helping employees to build their digital skills and confidence to use the tools they have and resolve their own problems

- Consider the overall digital employee experience and, where possible, streamline and simplify this so it’s designed around the needs of staff and not the structure of the organisation

- Build informal support networks to help resolve issues and unblock problems, and to share advice and learning with one another as it’s learned

- Managers understanding the role they play in unblocking barriers and creating a successful work environment – and leading by example

On reflection, it makes sense to roll this into the ‘Roles and skills’ theme we covered in the last session.

Conclusions

Across all of our themes there were some clear principles:

- Re-thinking how work gets done rather than translating existing office-based ways of working to digital channels

- Taking a user needs-focused approach, understanding barriers to effective distributed/remote working and how these can be ameliorated

- Helping people build their skills in communication and collaboration so they can embrace asynchronous working

- Trust underpins all effective remote working. Organisations must look at how this can be built and sustained at scale and for the long haul.

In his WB40 podcast, Matt talked to Dave Coplin about his recent research. Coplin found trust for managers in their employees was important, but so too was trust in peers. Managers need to know that work is being done (and done properly) and employees at all levels need confidence that their peers are pulling their weight too.

Measuring productivity in knowledge workers is notoriously difficult. Very little work can easily be attributed to outcomes, forcing us to measure outputs and throughputs instead (particularly in public sector organisations, where there may be pressure to demonstrate value for money). But such measurement is largely inaccurate (as anyone who receives weekly emails from Microsoft’s MyAnalytics can attest) and open to being gamed.

Striking the right balance between demands for productivity monitoring, sentiment analysis and creepy employee surveillance presents one of the first thorny challenges organisations face as they move from recovery mode to the long haul.

The two whiteboard sessions enabled us to evolve our model a little. Here’s version 2. It’s still a work in progress and we’re keen to get your thoughts on how it can be improved. Let us know in the comments.